Relieve Breastfeeding Pain: Solutions for the Moms Top Breastfeeding Struggles

Tender and sore nipples are normal during the first week or two of your breastfeeding journey. But pain, cracks, blisters, and bleeding are not. Your comfort depends on where your nipple lands in your baby’s mouth. And this depends on how your baby takes the breast, or latches on.

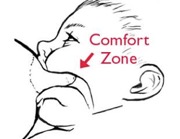

To understand this better, use your tongue to feel the roof of your mouth. Behind your teeth are ridges. Behind the ridges the roof feels hard. When your nipple is pressed against this hard area in your baby’s mouth, it can hurt.

But farther back in your mouth the roof turns from hard to soft. Near this is the area some call the comfort zone. Once your nipple reaches your baby’s comfort zone, breastfeeding feels good. There is no undue friction or pressure that would cause sore nipples during breastfeeding.

To make this happen, let gravity help. Lean back with good neck, shoulder, and back support and your hips forward. Lay your baby tummy down between your exposed breasts. When your calm, hungry baby feels your body against her chin, torso, legs, and feet, this triggers her inborn feeding reflexes. When her chin touches your body, her mouth opens and she begins to search for the breast. In these laid-back positions, gravity helps the nipple reach the comfort zone.

In other positions, you need to work harder to help your baby take the breast deeply.

- With your baby’s body pressed firmly against you and her nose in line with your nipple, let her head tilt back a bit (avoid pushing on the back of her head).

- Allow her chin to touch the breast then move away.

- Repeat until her mouth opens really wide, as wide as a yawn.

- As she moves onto the breast chin first, gently press between your baby’s shoulders from behind for a deeper latch.

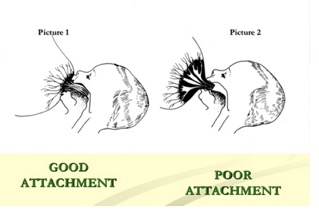

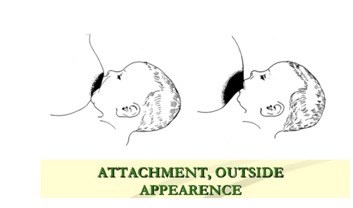

That last gentle push helps the nipple reach the right spot. Breastfeeding tends to feel better when your baby latches on asymmetrically, so that more of the areola (the dark part around your nipple) under the nipple is in her mouth than on top of the nipple.

Signs of a Deep Latch

- You feel a tugging but no pain throughout the breastfeeding session. (In the first week or so you may feel some pain in the first minute or two of sucking that eases quickly)

- You hear your baby swallowing.

- Her lower lip is rolled out.

- You see more of the dark area around the nipple above your baby’s upper lip than below.

- Your baby breastfeeds with a wide-open (not a narrow) mouth.

If breastfeeding hurts, seek help right away from a board-certified lactation consultant (IBCLC). The sooner you get help, the better.

Unicef WHO, breastfeeding promotion and support in a  bay friendly hospital, training course

Solutions for Sore Nipples

If you have painful, sore nipples during breastfeeding (beyond the first minute or two of discomfort that sometimes occurs) you need to take your baby off the breast and try for a better latch. Be sure to break the suction first. Gently slide a clean finger between baby’s lips and gums until you feel the suction release.

Even mothers with broken skin on their nipples can heal while breastfeeding. When their nipples reach the comfort zone, there is no friction and pressure.

If your breasts are very full and taut, it may help to express a little milk first. It is easier for a baby to draw a soft breast back to the comfort zone than a firm, full breast.

If after working to get a deeper latch, you aren’t feeling better within a day or two, seek help from a board-certified lactation consultant. Other solutions may be needed with other causes of nipple pain.

If you have broken skin on your nipples, products that provide a healthy moisture balance will help soothe sore nipples. Mothers were once told to keep their nipples dry, but now moist wound healing is recommended.

See our nipple moisturizing products. Helpful products include: Hydrogels